SEPTEMBER 2020

State of Play – guest essays from leading voices in Australian theatre

READ MORE OF THE STATE OF PLAY COLLECTION

This work was originally commissioned for the end of 2019. It arrived in my inbox just before huge fires began to rage around the country. In early 2020, Vanessa and I talked and she decided to shift the work a little in response to smoke in the air and masks on the street (sadly not the last time in 2020) and we set a publishing date. Then Covid hit. The world shuttered and everything seemed to go into suspension – should we still publish? Of course. So here we are now, with this personal, moving and crystal clear piece that seems ever more important from the middle of a different crisis. Enjoy the final State Of Play for 2020.

John Kachoyan

Playwriting and the personal.

Very much like.. say…well…a play, for some reason I’m finding it really difficult just to sit down and write this thing.

Yeah, that familiar nightmare. Writer’s block.

…Courage

Who’s that bongo…

…Can Never Be Cast

Three things said to me. Three things I’m sharing with you.

See what I mean?

It doesn’t even make sense.

It’s not just because it’s still school holidays and Tricky (aged 13) and I are going through some ahem difficult patches.

This morning he said he doesn’t understand me AT ALL and I said yeah well, I understand you ALL TOO WELL. I have no idea what that means either and soon we were both shouting at each other which means, of course, I lose, being the parent.

Then there was the heat and the smoke.

And the storms.

And the fires.

And that thing with the bird.

Once, Edward Albee signed a copy of Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf for me.

He wrote; From one playwright to another…Courage.

He didn’t write this in a newly bought copy of arguably his most famous play, he wrote it in a hand-me-down copy, it was slightly shabby and dusty and faded, and it had belonged to my mother which made it multiply precious.

At the time it seemed an odd thing to write. Courage.

Like, a call to arms or a battle-cry. As if he expected me to take up an axe or perhaps a fence paling studded with rusty nails against say…Bullshit Non-Representation of Women Playwrights on stage or glaringly obvious and Rather Embarrassing Lack of Diversity in Top Tier Jobs in Theatres.

I’m not a particularly courageous person, I thought at the time. To be honest, I’m quite short, shy and also a bit of a wuss.

Frankly, I’d have been happier if he had written something useful like: Hey! Your Play Rocks and I should Know!

It was the second time I’d worked with Edward Albee, this time on my play Every Second. Every Second is a blackly comic four hander about infertility and anger. At the time Edward told me to take a good hard look at a plotline I’d jemmied into place and suggested it was unnecessary. But I need it, I whined, otherwise the plot’s basically only about what the female characters want and try to get.

So? Isn’t that enough? he asked.

He was right. Why did I think it wasn’t enough? Apart from the fact that it was a female character, and also based slightly on my own infertility experience. It was almost as if I felt that I wasn’t good enough, wasn’t playworthy enough.

I probably thought there would be a third time to work with Edward and this time I’d be confident enough to brandish my female oriented me-centric new play and I could encourage a more relevant or at least a more directly marketable quote.

Sadly, there was no third time. For anyone.

So, the bird thing.

Ok, what happened first was I saw the blackbird in the back garden. A European Blackbird my arborist neighbour told me, that’s interesting they’re not common, but I already knew it was both special and uncommon because I had been fully educated in the Enid Blyton Flora and Fauna Literary Canon (what I could tell you about bluebells!) and thus as well as talking toys and trees that lead to faraway magical lands, I also knew about old fashioned English garden creatures. Like blackbirds.

This bird was shiny and black and its beak was long and bright orangey gold. This meant it was male and also had at one point dipped its beak in Pip the pixie’s barrel of gold paint. I didn’t tell this stuff to my neighbour. One doesn’t. Anyhow, next thing, Mr Blackbird turned up with a much dingier, non-pixie golden beak Mrs.

This led to a nest made of stolen Spanish Moss on the 4×2 holding up the edge of the carport, and several anxious weeks later this led to eggs. Four. I know this because I climbed a ladder, hung onto a drainpipe, draped my phone over the 4×2 and took a photo of these eggs in the nest while Mrs B was out foraging, and it pleased me these eggs, these four beautiful eggs, full of promise and chicks. The back garden can be a dark highway for neighbourhood cats, there have been rat sightings, small children from next door brandishing nerf guns, currawongs aka ‘pirates of the backyard’ pop in now and then, all of these are deadly to eggs and baby birds and small adult birds who don’t keep a beady eye out, but these Blackbirds, Mr and Mrs, were awesome and aware and awake and other good things that start with aw.

But then the heat.

The sun, bright shining star, delightful smiling friend of pixies and blackbirds alike in those Blytonesque country gardens, became in November a glowing red Satanic arsehole, boiling and bubbling in the sky. My poor Birds. I hosed down the carport, all the time feeling guilty because …water, right? but the eggs, the four beautiful eggs, they were in danger of baking, on my watch. I saw Mrs Blackbird, seated staunchly on her Spanish Moss nest, open her dull drab beak to the beads of hose water dripping off the roof and onto her.

And then the fires. Dear god. Did anyone before these days know that koalas scream as they burn alive? Can any of us say we had ever imagined that sound?

Then I went to Sydney, on New Year’s Eve, not the on fire bits but still an actual hellmouth, hot and windy and smoky and I spent the night indoors watching episodes of Succession in between turning to bushfire coverage. It was both inspiring and depressing. Here… a masterful verbal stoush, there a koala bear screaming. And fireworks. Because, well because Sydney.

Who’s that bongo you’re waving at?

Penang.

I was in grade 5 when a kid on the school bus, the bas kilang, asked me this. It was my first day at this school, Grade 5, the RAAF school, Penang, Malaysia. It was the late 70s. Every week there was a different religious holiday. Monkeys lived in the trees. Horseshoe crabs rolled like tiny tanks across the sand. My sisters and I could run riot. It was perfect. Except for one tiny difference.

The term “bongo” like “noggie” and also “rockape” was used by other Australians to describe the local people. The brown people. Chinese, Malays, Indians.

The kid asking was older than me. Like me he was dressed in a white RAAF school uniform. The whole bus was full of kids in white RAAF school uniforms. White kids in white school uniforms. But me and my sisters were brown. Like our mum. Who was standing on the footpath and smiling encouragingly. Hey girls, another new school, it’s ok, be brave.

My mum, I said in a scared voice, the voice of a kid who doesn’t want to be different, who wants to be invisible, who wants to fit in.

I’m waving at my mum.

My mother was from the Philippines. She arrived in Sydney in the mid 60’s as a nursing student. She was the eldest of a family of four. She flew on a QANTAS fly now pay later scheme. She sent money home to her family. For her first pay she bought her mother a watch and sent it back to the Philippines. It never arrived. She met my dad, in hospital when he had just joined the RAAF, English migrant, only child, ripped the ligaments in both knees in nasty soccer accident. They probably made meaningful eye contact as she swabbed his patella. I’ve seen the photos. Both. Cute as. He’s white, she’s brown.

I too was the eldest of four, all girls. I was quiet, I looked and I listened. I wrote stories, an early opus involved an ant, a plant and an elephant. I read a lot. But I didn’t speak out a lot and I like to say the main reason was because I was a writer and writers don’t like to be up front. They quietly observe shit and they go write it down. But the other reason I think was because I was both brown and a girl. I wanted to be integrated and invisible.

I think back and I wish I’d been one of those feisty girls.

Those girls in the books I loved as a kid.

Jo from Little Women. I loved Jo’s spirit, but I knew deep down I was actually a tepid, sickly sweet Beth.

Or… Elizabeth, troubled star of The Naughtiest Girl In School, known for hot tempers and furious rages and slapping rude boys across the face but really I was more like Joan, Elizabeth’s mousy friend.

Katy from What Katy Did thrilled me to the core with her fearsome rendition of a roaring Father Ocean in the middle of her 19th century schoolroom, but it was the more sedate sister Clover that I resembled.

Also, Katy ended up paralysed for quite a long time – falling off the shed roof I think – and had to learn humility and the feminine art of being sweet. Interestingly, Judy in Seven Little Australians doesn’t take bullshit but I seem to remember that quite early on a rather large piece of tree falls on her and breaks her back.

I read a lot of books as a kid and I liked a lot of stories about feisty brave girls but the truth is I can’t remember a single feisty girl who was also brown. Oh wait yes I can. Carlotta in Claudine at St Clare’s. She was rude to the posh girls and also prone to slapping and she could walk on her hands. She wasn’t the star though.

The first scripts I wrote for performance were comedy sketches for the university review.

I didn’t start off writing sketches,..like every pert first year drama student, I wanted to be an actor. At some point I complained to the director about the terrible roles being written for women – harried housewives and various prostitutes with setup lines, no payoffs. And small parts in the chorus of parody songs, as I sang with gusto, not any actual talent.

Fine, said the director, you want better parts, write them yourselves. Ok I said, ever so slightly shocked at the very idea. Me write something that people had to perform? Outrageous! But I did.

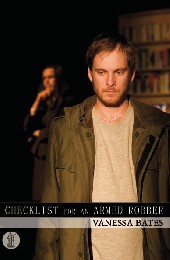

This led to me getting my first after uni job writing theatre in education plays; Wishful Thinking and her is the beehive and then writing a play about a girl who gives birth to a fish; Darling Oscar which was picked up by the STC and on I went, writing, stressing, fretting, writing some more. I wrote about couples having sex and eating cake; PORN.CAKE and youthful armed robbers juxtaposed with older booksellers Checklist For An Armed Robber. I wrote about fairy tales told by marginalised female characters The Magic Hour and I wrote about the anger in infertility Every Second.

So here’s the other thing that was said to me, early on in my playwriting career and stayed with me.

This is a good play but it can never be staged because we can’t cast it.

This play, shortlisted for a major award, was about many things but at its heart it was my story, about me and my Eurasian sisters and our mother from the Philippines who dies of breast cancer.

We can’t cast it.

Were there Eurasian actors then? Were there Asian actors? It was 2003 for fucks’ sake, of course there were, just because you didn’t see them, didn’t know about them, didn’t hear from them. They were there.

And what does this do to a youngish Eurasian playwright who has come to Sydney from Newcastle, who has had a few successes, enough to keep her hopeful, keep her trying but not anywhere near enough to establish her, certainly not enough to cast her play, stage her story, that is predominantly non-white? She smiles, steps back, mouse-like, Joan and Beth like, recognises…your story can’t be staged. So don’t write it. Write a different play. Write another play. Write something else.

In 2020 when I got back to Newcastle, post New Year’s Eve and the Inappropriate Fireworks, I wanted to see what was left of the Blackbird family. There had been no bushfires in Hamilton per se, but it had been very fucking hot. The birds were there and to my great amazement, there were two chicks alive and peeping and Mr and Mrs B with beaks full of freshly regurgitated insect soup, doing their feeding and fussing thing just like the Enid Blyton stories and it was frankly delightful.

I did write other plays. And these did get staged and they were awesome experiences because, we’re playwrights, we want to write plays and we want to work with creatives and see those plays staged. And in every play there were bits of my mum and bits of me and bits of my sisters, little bits, but never that play.

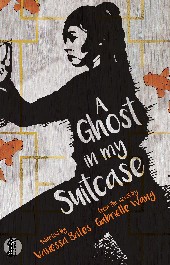

I want to jump sideways now. Another year. Another play. Four years ago I was commissioned by Barking Gecko Theatre Company to write a play adapted from Gabrielle Wang’s novel A Ghost In My Suitcase. It’s a story about a girl named Celeste, half Chinese, half French, who goes to China to stay with her grandmother (Por Por) and to scatter her mother’s ashes. While in China Celeste learns some surprising truths, about her mother and grandmother, and about herself.

Celeste was not a spirited girl like Jo March, or a feisty girl like Elizabeth Allen or even a bad tempered Katy or a plucky Judy. Actually I take that back because in a way at different times, Celeste was all those things. But she also listened and watched. Like a writer. Like me. And the death of her mother and the camphorwood chest and the ghosts all chimed with me.

Casting wise, this play, had a grandmother (Chinese) a teenage girl (Chinese) a Eurasian girl (“half Chinese, half French, all Australian”). As well as the main three Asian or Eurasian actors, the play also required two more Asian actors, one male, one female, to play other roles. The lead actor in the first stage of workshops had to leave and a new Celeste had to be found. Directors Matt Edgerton and Felix Ching Ching Ho worked hard to cast the play, looking at actors in Sydney, Perth, Brisbane and Melbourne. The play was produced in Melbourne, Sydney and Perth International Festivals.

The first reading of an early draft of the play in a workshop setting at Barking Gecko in Perth, was surprisingly emotional. Probably not surprising for anyone who knows me, as I cried during The Incredibles and at that duckling in the Kleenex ads and also when I see random people applauding buskers at Central station. But this time it was because I saw a table of strong beautiful brown women, reading a play that I had written.

So as you can imagine, when I actually saw the play open at the Victorian Arts Centre, and being performed at the Sydney Opera House, and at Perth’s Heath Ledger Theatre it was a hundred kinds of special. There was great response from kids and teachers and parents.

And there was this comment:

“I was struck by the feeling of wanting to cry simultaneously while I was beaming from ear to ear….Experiencing your difference as an identity is powerful… As a child of mixed race in Australia, at times I felt, or was made to feel, like my identity was nothing….To see Celeste’s strength as a Eurasian woman was stunning…”

In 2020 I’m writing a new play commissioned by The Ensemble theatre in Sydney. It’s the story of a Eurasian girl and her Malaysian mother and an uncomfortable reunion in a Chinese restaurant. It’s not that play, the one about me, the one about my mother and my sisters.

But it’s closer to me. Here’s the thing. You can spend your entire life writing out your passion, your love, your rage, your hope and sometimes you feel like you’ve taken giant writer’s steps and sometimes you took tiny wandering ant, plant, elephant steps but they’re all heading in the same direction, and you keep moving, you keep trying and above all, you keep writing. To get closer.

Courage.

Back in the carport, one chick fell out of the nest but I picked it up and climbed up the ladder and put it back in the nest and I felt like a goddess.

Yes, yes, a tired, middle aged peri-menopausal goddess with writer’s block but still, goddess like.

I couldn’t save the koalas but I could save one fluffy baby bird.

It wasn’t a play, it wasn’t a Succession type witty verbal exchange but it was a positive moment and it was life affirming and I felt like a good parent and a courageous woman because hey, that beak was sharp, and also those parent birds were circling me like a pair of tiny angry harpies and they were ready to swoop in and pluck out my eyes.

Somewhere, somehow, in a parallel universe a long way away and just the other day, a small brown girl in a white school dress on a bus calmly loses her shit with a bigger boy.

She picks up the fence paling that conveniently springs to hand and runs her fingers over those lovely sharp nails. She thinks about slapping his face. She thinks about walking on her hands. Two blackbirds swoop down and attempt to peck out his eyes with beaks of pure gold. The brown girl turns and looks proudly through the glass at the beautiful young Filipino woman standing on the pavement with one arm held high.

And as the bus pulls away from the kerb, they wave and wave and wave.

VANESSA BATES

Vanessa Bates is an award-winning playwright for stage and radio and also writes for film and television. Her plays include Trailer, Light Begins to Fade, Every Second, The Magic Hour, PORN.CAKE, Checklist for an Armed Robber, Chipper and Darling Oscar. She adapted A Ghost in My Suitcase for Barking Gecko Theatre, Melbourne International Arts Festival 2018, Sydney Festival 2019 and Perth Festival 2019. Her plays have been produced by the Sydney Theatre Company, Malthouse Theatre, Belvoir B-Sharp, Griffin, Vitalstatistix, Ensemble Theatre, atyp and Tantrum Theatre, among others. Her work has won a NSW Premier’s Literary Award, AWGIE Award, Inscription Chairman’s Award and Inscription New Work Award and has been shortlisted for the Victorian Premier’s New Play Award, Griffin Award and STC Patrick White Playwrights Award.

She is 1/7 of playwriting alliance 7ON.

ALSO BY VANESSA

-

A GHOST IN MY SUITCASE$23.99

A GHOST IN MY SUITCASE$23.99 -

EVERY SECONDPrice range: $5.40 through $15.00

EVERY SECONDPrice range: $5.40 through $15.00 -

TRAILER$23.99

TRAILER$23.99 -

PORN.CAKEPrice range: $5.40 through $19.00

PORN.CAKEPrice range: $5.40 through $19.00 -

Checklist For An Armed Robber$23.99

Checklist For An Armed Robber$23.99